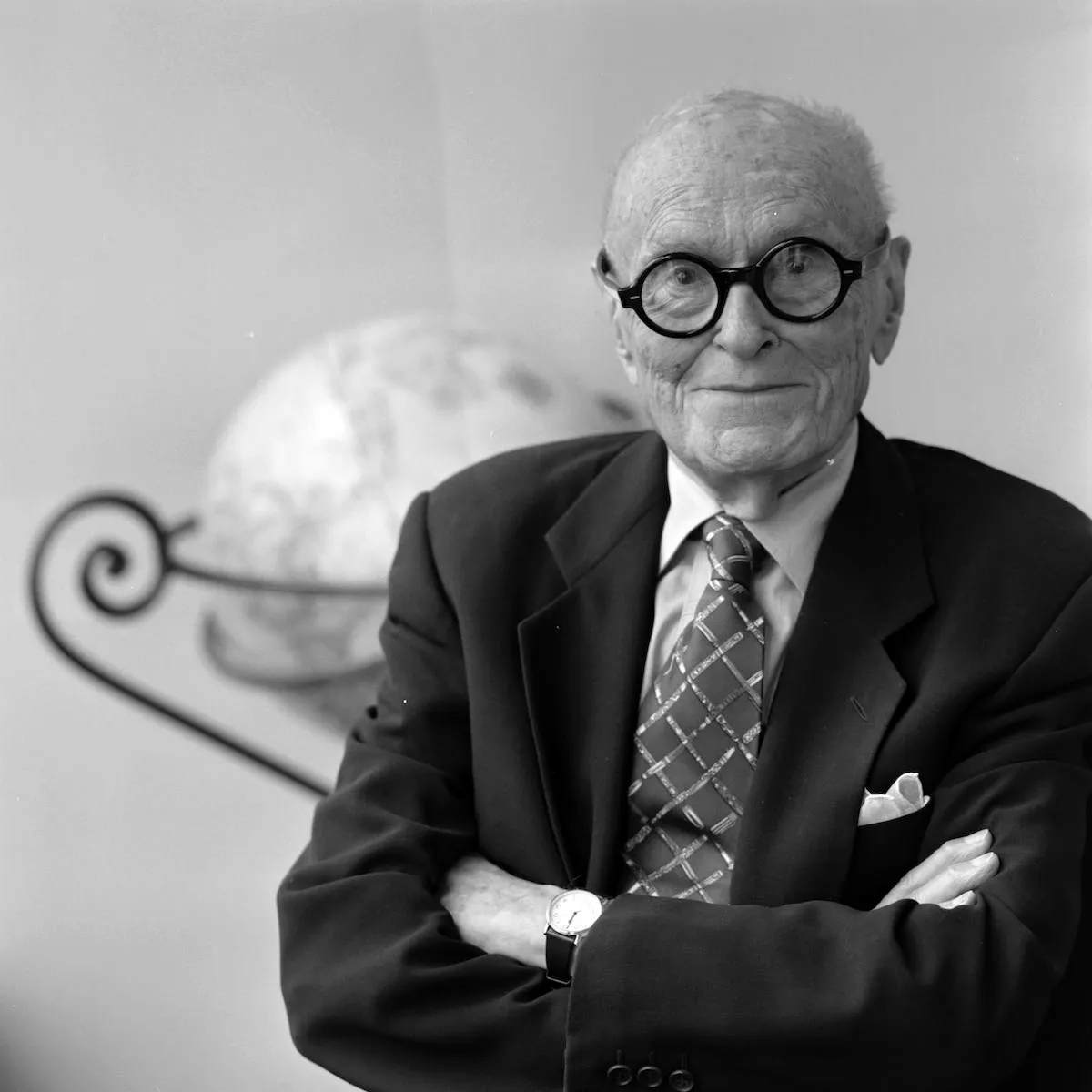

Full Name: Johnson, Philip

Other Names:

- Philip Johnson

Gender: male

Date Born: 08 July 1906

Date Died: 25 January 2005

Place Born: Cleveland, Cuyahoga, OH, USA

Place Died: New Canaan, Fairfield, CT, USA

Home Country/ies: United States

Subject Area(s): architecture (object genre), Modern (style or period), and sculpture (visual works)

Career(s): curators

Overview

Architect and first curator of the department of architecture of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1932. Johnson was the son of a wealthy Cleveland attorney Homer M. Johnson, and an equally wealthy and cultured mother, Louise Pope (Johnson). He entered Harvard in 1923 without taking the qualifying exam. The following year his father divided a large amount of his fortune between his children, his daughters receiving cash, and Philip given stock in Alcoa Aluminum. This was the source of a lifelong financial independence. Troubled by his emerging homosexuality, Johnson suffered several psychological breakdowns while at Harvard, intermittently traveling to Europe. Toward the end of his Harvard years (he finally graduated in 1930 with a degree in classics), two events changed his life. At about the same time, Johnson met Alfred H. Barr, Jr., a graduate student at Harvard who had just accepted the directorship of the Museum of Modern Art, and Johnson read an article by another Harvard student, Henry-Russell Hitchcock on the subject of modern architecture. Johnson may have been amorously attached to these men as well. Barr saw in Johnson’s wealth and enthusiasm the perfect person to lead a department of architecture in his new museum. Johnson and Hitchcock traveled to Germany in 1930 to study modern architecture for the Museum of Modern art. He returned with enthusiasm for modern architecture and, somewhat ironically, a glowing view of Adolf Hitler. In 1932, Johnson mounted the exhibition “The International Style,” with a catalog written by Hitchcock, who had coined the term, for the Museum. The exhibition was responsible for bringing modern architecture as a style to the minds of the United States’ public. Johnson left MoMA in 1934 to return to Ohio as a political activist. He and a friend, Alan Blackburn, worked for populist and fascist candidates in America such as Huey P. Long, the senator from Louisiana, and, after Long’s assassination, the Detroit radio broadcaster Father Charles E. Coughlin (famous for characterizing Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in anti-Semitic terms as the “Jew Deal”). Johnson returned to Germany to study the Nazi successes. He attended a Hitler rally in Potsdam in 1938, the co-called Sommerkurs für Ausländer in Berlin. His roommate was the journalist William Shirer (1904-1993), later author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Johnson followed the German army into Poland after the German attack in 1939, writing “We saw Warsaw burn and Modlin being bombed…It was a stirring spectacle.” In the United States, he helped organize a fascist party. In 1942, with the country deeply engaged in the war fighting fascism, Johnson decided to train as an architect, enrolling at Harvard’s graduate school of design. The school was led by the modernists architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. However, Johnson was closer to Mies van der Rohe. Johnson graduated in 1943, served in the U.S. Army, and after the war attempted to practice architecture on his own. Barr took Johnson back a his head of MoMA’s architecture department. He was joined in the department of decorative arts by Mildred Constantine. In 1947 Johnson mounted a show on Mies van der Rohe. In 1952, Johnson designed the sculpture garden for the museum (though later altered, refurbished in 2004 to its original design). In 1954 Johnson left the museum again in 1954 to return to practicing architecture. Between 1967 and 1991 he partnered with John Burgee to design many of the large buildings for which he is famous. These include a number of New York office buildings and the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks in Washgington, D. C. In 1988, in his mid nineties, Johnson returned to curation at MoMA with an exhibition on “Deconstructivist Architecture,” highlighting the work of Frank Gehry and others. Johnson died in his most famous residential architectural work, his Glass House at New Canaan, Connecticut, designed in the mid 1960s. Flamboyantly gay, his relationships were never a secret. His partner of the final forty years of his life was David Whitney. Johnson’s architecture has been criticized for being overly style conscious and indeed his building designs seemed to change with every new architectural fashion. His commissions comprised some of the most important ones in the United States. Peter Eisenman, in an introduction to Johnson’s Writings (1979) wrote that Johnson’s architecture was the “ideal model of a more perfect society.” Neither his designs or his architectural writing indicate a concern for the social or practical aspects of modern architecture.

Selected Bibliography

and Hitchcock, Henry Russell. The International Style: Architecture Since 1922. New York: W. W. Norton/Museum of Modern Art, 1932; Mies van der Rohe. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1947; Lewis, Hilary, and O’Connor, John, eds. Philip Johnson: the Architect in his Own Words. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1994; and Sombart, Werner. Weltanschauung, Science, and Economy. New York: Veritas Press, 1939; Eisenman, Peter, and Stern, Robert A. M, eds. [Philip Johnson] Writings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979; and Wigley, Mark. Deconstructivist architecture: the Museum of Modern Art, New York. New York: Little, Brown/New York Graphic Society Books, 1988.

Sources

Philip Johnson and the Museum of Modern Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art /Harry N. Abrams, 1998; Schulze, Franz. Philip Johnson: a Biography. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1994; Marquis, Alice Goldfarb. Alfred H. Barr, Jr.: Missionary for the Modern. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989, p. 84; [obituaries:] Saint, Andrew. “Philip Johnson: Flamboyant Postmodern Architect whose Career was Marred by a Flirtation with Nazism.” The Guardian (London) January 29, 2005, p. 25; The Washington Post February 2, 2005, p. A23; Applebaum, Anne. “Remembering Philip Johnson.” The Guardian (London) January 29, 2005, p. 25.